|

LOW RESISTIVITY PAY BASICS

LOW RESISTIVITY PAY BASICS

Low resistivity pay zones have baffled

many log analysts for years. The causes are usually quite simple but

we often have to twist our mindset a little bit.

The most common cause is fine to very

fine grained sandstones and siltstones coupled with low resistivity

(high salinity) formation water. This kind of reservoir has a

naturally high irreducible water saturation, often in the range of

40 to 70%. Lets take a couple of examples:

Assume RW@FT = 0.015 ohm-m.

Case 1: RESD = 3.0 ohm-m, Vsh = 0.00, PHIe = 0.24

RWa = (PHIe^2) * RESD = (0.24^2)) * 3.0 = 0.0864

SWa = (RW@FT / RWa)^0.5

= (0.015 / 0.0864)^0.5 = 0.42

This is typical of many fine grained sandstone / siltstone reservoirs.

Case 2: RESD = 4.0 ohm-m, Vsh = 0.00, PHIe = 0.12

RWa = (PHIe^2) * RESD = (0.12^2) * 4.0 = 0.0576

SWa = (RW@FT / RWa)^0.5

= (0.015 / 0.0576)^0.5 = 0.51

This is typical of the Bakken sandstone / siltstone in Saskatchewan.

In these two examples, the logs determines the saturation. Grain

size determines that both wells produce clean oil with little water.

The same log values in medium or coarse grained rocks would produce

water with or without some oil. The numbers are just "answers". It

is still up to you to interpret the answers by integrating them with

everything else that is known about the rocks. Oil staining, oil on

the mud pit, nearby oil production, a production test - all count

toward a final understanding of a well's potential.

Many people look at the resistivity value thinking it is below their

limits (or their ego) and forget to consider the porosity and water

resistivity effects. Once this simple calculation has been done, and

production has been proved, the "resistivity cutoff" can be

established. But use caution; the cutoff varies with porosity.

Two other situations produce low resistivity pay zones - laminated

shaly sands and laminated porosity variations. These are discussed

HERE.

LOW RESISTIVITY feLDSPAR SAND

LOW RESISTIVITY feLDSPAR SAND

Here

is an example of a radioactive interval that needs a quick look

analysis. If you think like a detective, the answers usually come to

light. Gather the evidence, assess the evidence, discard the

impossible, select the most probable from what remains. In general,

the simplest solution is often the best choice.

We have a

zone

that is radioactive and looks like a shale on

the gamma ray log. The density neutron porosity curves on sandstone

scale however show zero separation, so this interval cannot be a

shale. This lack of separation is correct foe quartz or feldspar

sand. It is radioactive so it can't be quartz, so feldspar it is! We have a

zone

that is radioactive and looks like a shale on

the gamma ray log. The density neutron porosity curves on sandstone

scale however show zero separation, so this interval cannot be a

shale. This lack of separation is correct foe quartz or feldspar

sand. It is radioactive so it can't be quartz, so feldspar it is!

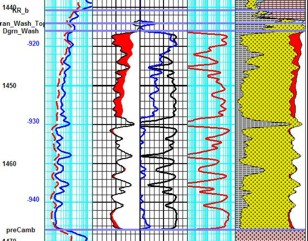

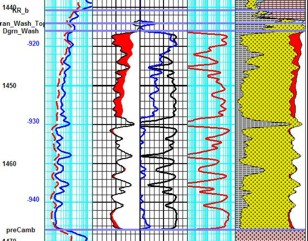

Composite raw

data plot for radioactive feldspar sand

This example has no gamma ray

spectral log. It would have been a help, but is not essential since we know

the area and the density neutron curves answer all the

questions about porosity and lithology.

There is a second issue though,

and that is the low resistivity over most of the sand interval.

suggesting a water zone. The highest resistivities are in tight

anhydrite and dolomite above the sand. The best resistivity in the sand is just 2

to 3

ohm-m in the top 1.5 meters of the sand and the water zone is 0.4 to

0.8 ohm-m, a contrast of about 4:1. An old

rule of thumb suggests that a ratio of 3:1 or better means we should

complete the well, as long as the porosity is about the same in both

the water and oil legs.

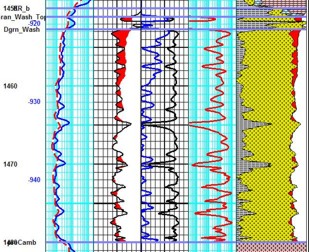

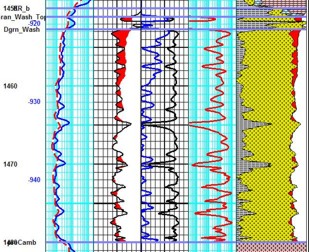

A test on the top of the sand in

the well on the left, below, produced clean oil, but water cut

increased after about six months production. A second well at the

right was drilled and tested water with some oil. The resistivity

log signature is only very slightly different than the first well.

Visually there is not much difference between them.

Detailed

petrophysical analysis does show subtle differences. The well on the

left shows a 2 meter pay zone on either a long transition zone or a

depleted oil zone of about 7 meters. The second well shows only a

half meter of pay on top of the same transition zone. The test and

production results are confirmed by the fluid distribution in the

two wells. And there is not much that can be done to improve the oil

production.

Actual saturation (blue curve in

Track 3) compared to irreducible water saturation (black curve) in

two wells. Where the two curves are close together, little water

will be produced at initial completion. Where they are separated,

water will flow with the oil. Production histories on these two

wells bear out this interpretation: the well on the left produced

clean oil for six months, the other tested water with oil

immediately.

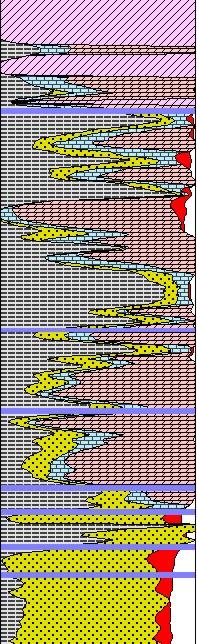

A

good wellsite geologist will correlate his description to the

shape of the drilling time log. Later, the sample depths may be

adjusted to the open hole logs, especially gamma ray, resistivity,

and density logs. In this pair of wells, the first hint of the

feldspar sands is in the wellsite sample descriptions as shown

below.

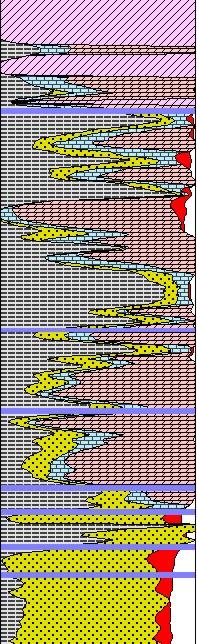

Log analysis lithology plot (left) in a complex sequence, and sample

description plot (right) over the same interval.

Although the lithology description is not usually quantitative,

it is an essential ingredient in choosing the correct mineral

mixture for the log analysis lithology calculation. A little

care is needed to read these logs. In this case, the word "SAND"

describes the rock texture, not its mineralogy. This is a

radioactive sand so it must contain feldspar (decomposed

granite) and possibly some quartz, as well as the dolomite and

anhydrite layers above the sand. Shale, of course must be

handled by an appropriate method. In this case, shale cannot be

found using the GR inside the radioactive sand interval.

LOW RESISTIVITY RADIOACTIVE SANDSTONE / SILTSTONE

LOW RESISTIVITY RADIOACTIVE SANDSTONE / SILTSTONE

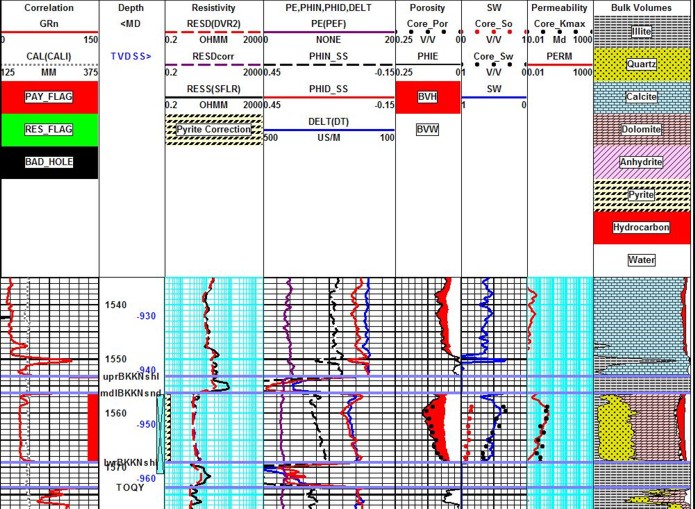

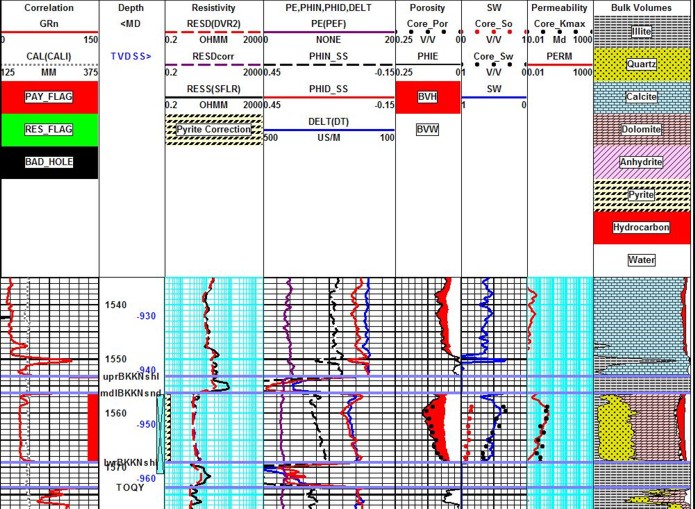

Again we will use our detective skills to sort out the

conflicting evidence from the logs shown below. This is a Bakken

Sand interval with the Upper and Lower Bakken Shales bounding the

sand/silt interval. These shales have very high organic content and

are the source rocks for the oil in the Middle Bakken Sandstone.

They are also very radioactive, more than 300 API units. This is a

clue that uranium may be present as most shales seldom exceed 150

API units.

The sand is also radioactive, averaging 120 API or higher. The

potassium, thorium, and uranium curves are in Track 1 with total

gamma ray. Uranium content is roughly constant in this example,

giving a constant shift to the total GR counts. The thorium curve

shows some character but samples and core description indicate clay

volume is less than 5%, distributed as burrows and microscopic

discontinuous bands.

The density neutron porosity on a sandstone scale is sufficient to

indicate dolomite, but the samples suggest a dolomitic quartz sand.

Further investigation with XRD shows a 50:50 mix of quartz and

dolomite with a few percent pyrite. The pyrite is sufficient to push

the neutron porosity a little bit higher and the density porosity a

little bit lower, increasing the separation enough to mimic the

dolomite effect. Porosity is still halfway between the density and

neutron porosity and no shale correction is needed.

The resistivity in the shales is quite high and the sonic, density

and neutron all read high, suggesting coaly material. The PE curve

disputes this as coal would be less than 1.0 and these shales have a

PE of more than 3, representing the mix of clay, silt, and kerogen.

The resistivity in the sand is only 3 or 4 ohm-m, which looks wet.

But the very fine grained sand and silt have naturally high

irreducible water saturation. This, coupled with a saturated-salt

formation water, end up giving a water saturation between 40 and

50%. Clean oil production with small water cut proves the case.

Deeper in the basin, the rock becomes more calcitic instead of

dolomitic, porosity decreases, resistivity increases, and the zone

looks more "normal" but it is still just as radioactive. CAUTION:

along the northern edge of this play, water resistivity increases

significantly, leading to 15 ohm-m sands that are 100% wet.

But it took 50 years from the first producing well to convince oil

company management that this would become the largest oil field in

North America. New technology, in the form of horizontal wells and

massive hydraulic fracturing jobs, helped turn the mindset around.

Bakken “Tight Oil” example has no kerogen in the productive sand /

silt section but very high kerogen content in the shales above and

below. Zone is radioactive due to uranium carried from the source

rocks during oil migration. Log example showing core porosity (black dots), core oil saturation (red dots).

core water saturation (blue dots), and permeability (red dots). Note

excellent agreement between log analysis and core data. Separation between red dots and blue

water saturation curve indicates significant moveable oil, even

though water saturation is relatively high (see text below for

explanation). NOTE that the organic rich Upper and Lower Bakken

Shales are much more resistive than the Middle Bakken Sand/Silt pay

zone due to the high TOC content in the shale. There is no

significant kerogen in the sand itself.

|

We have a

zone

that is radioactive and looks like a shale on

the gamma ray log. The density neutron porosity curves on sandstone

scale however show zero separation, so this interval cannot be a

shale. This lack of separation is correct foe quartz or feldspar

sand. It is radioactive so it can't be quartz, so feldspar it is!

We have a

zone

that is radioactive and looks like a shale on

the gamma ray log. The density neutron porosity curves on sandstone

scale however show zero separation, so this interval cannot be a

shale. This lack of separation is correct foe quartz or feldspar

sand. It is radioactive so it can't be quartz, so feldspar it is!